ANDER MCINTYRE: PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY OF “AN” ESTABLISHMENT, WITH DIPLOMACY BUT NO GLAMOUR. AN INTERV

- Fernando Gómez Herrero.

- Jul 22, 2020

- 10 min read

ANDER MCINTYRE: PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY OF “AN” ESTABLISHMENT, WITH DIPLOMACY BUT NO GLAMOUR. AN INTERVIEW WITH FERNANDO GOMEZ HERRERO.

Photography included used with the permission of Ander McIntyre for Culture Bites.

It is initially in relation to the project for Chatham House (https://www.chathamhouse.org/room-hire/portraits), that I approach Ander McIntyre with a few questions about the moving power of photographic images in the vicinity of “an” or “the” establishment of international relations in the vicinity of the British think tank in the centenary anniversary of its creation. This exhibit, currently under covid lockdown, must be put in the larger context of his work (https://portraits-of-an-establishment.com/). And there is a second comparable exhibit at the British Library (https://www.bl.uk/events/the-eccles-centre-for-american-studies-a-25th-anniversary-celebration-in-portraits) among other projects. I remain interested in the creative process and how these beautiful photographs come into being. McIntyre speaks of the imperative of diplomacy and yet he summons the image of the pickpocket who is about to capture something other than “the pose.” What is it about the genre of the portrait of “the” or “an establishment that attracts him? He speaks of “people who create, and make, and change society” and there is latitude here.

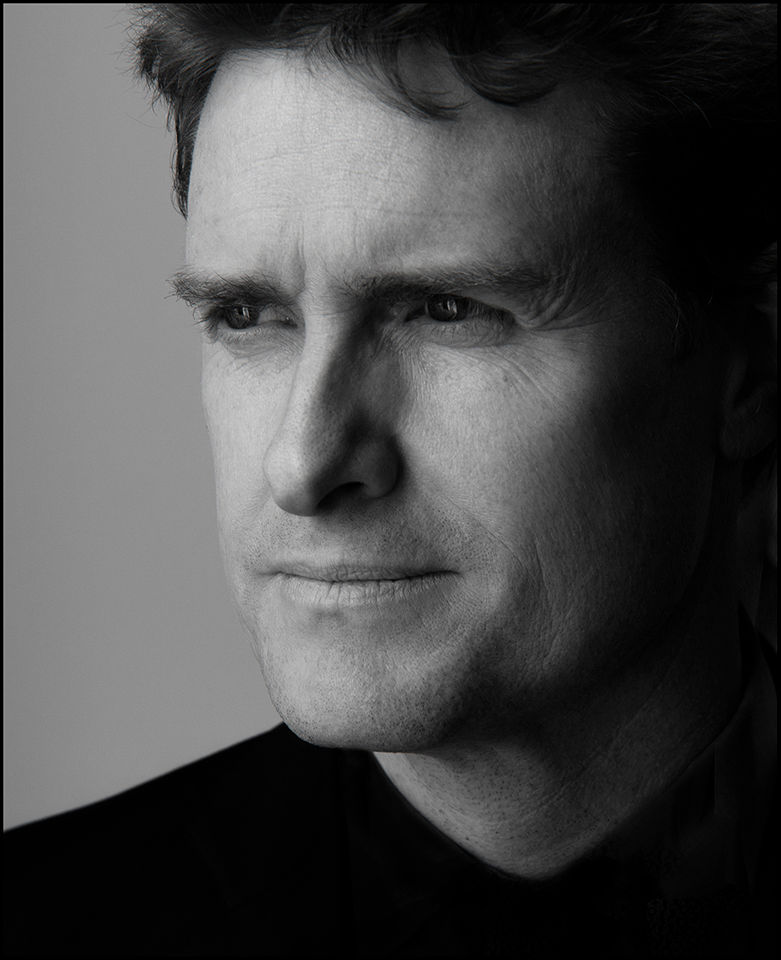

Joe Biden, © Ander McIntyre.

Particularly in the vicinity of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, we have something of the excitement of global politics. And we also have something of the erotica of power and influence that is never far away from the “dirt” of politics (the Italian language is eloquent, “erotica del potere” and “porca politica”). But these photos are consistently good-looking even if the individuals chosen are not necessarily all good-looking per se. You and I could be perhaps there too. McIntyre talks about the process and selects three photographs (Joe Biden, Kofi Annan, Rev. Lucy Winkett). He allows us to use four more (Katrin Jakbosdottir, Prime Minister of Iceland, the great intellectual Noam Chomsky, Tristam Hunt, former MP, now Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum and Emma Sky, expert of conflict resolution, former adviser to General Odierno in Iraq; https://www.fernandogherrero.com/single-post/2017/07/18/Perhaps-the-Unraveling-of-Emma-Sky). He allows us to use these photographs and his aforementioned website includes many others. There are recognizable figures in high places, Queens, Kings and Princes, and also prime ministers and high state officials and political representatives. And there are also writers, actresses, film-makers, journalists… So, there is a certain opening of the social aperture, even if we are dealing with the isolated figure in no particular landscape, often with the close-up of the total or partial face. It is often black-and-white and there is also colour. The treatment is always, I find, respectful, perhaps we can even call it ethical. Is this the capture of a diplomatic pickpocket? Using the language of Emmanuel Levinas, we as viewers enter something like a face-to-face encounter with the Other via this photographic mediation. Yet, McIntyre shows a willingness to stick to the neutrality in the politics of photography. Is photography political? Is this photography political? And how do we understand the p-word in relation to the static image of a close-up facial portrait sometimes in black-and-white? A final question remains, for me, whether portrait photography is in and of itself a more “conservative” genre at least in some circles not far from London, than, say, documentary photography such as the Magnum Group (https://www.magnumphotos.com/), currently struggling to stay relevant in the accelerated digital age of moving image consumption, fake news and the rest. There is a quietness in McIntyre’s photography, a recollection of a person in tranquillity, perhaps the illusion of intimacy. And I mean the previous adjective in question marks (“conservative” in between the political and the artistic) in the sense that it appears to elevate the already elevated, like a menina serves the princess in Velázquez’s famous Baroque painting, fair or unfair? He did not want his own portrait to go here, adding that he was less lovely than the Prime Minister of Iceland. These are his words.

FGH: What was your background and training? I see that you read English at Oxford and worked for the Oxford English Dictionary for 23 years.

AM: I had a very Catholic, boarding school education (De la Salle brothers and Jesuit priests). I am still waiting for the “twitch upon the thread”. First choice at Oxford was a mixed college, after years of single-sex education. As yet, no appearance of cameras. I went on to study Renaissance English drama at the Shakespeare Institute in Birmingham, and began to make exceptionally awful short films.

After several failed novels, plays and screenplays, I worked for the OED, specialising in the vocabulary of the odd, bizarre and ephemeral. Reaching into the past to find new material. The Dictionary is moving beyond recording the language of Shakespeare and Jane Austen, and I read, in the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the British Library, a great deal of ‘wrong’ science, early sixteenth-century travel narratives, and seventeenth-century newspapers.

At the same time, I wrote and made a living from stories and serials for teenage girls’ magazines. No cameras so far - this began with educational publishers in Oxford. I would photograph for school textbooks - children staring intently down microscopes, fork-lift trucks, a fair amount of ‘right’ science, thanks to the Oxford Science Departments. The challenge here was to get a list of picture needs in the morning, find where I could photograph an electron microscope, get a nice shot, cycle to the processing lab, take the transparencies to the publishers by four. And (with luck) be given the same the next day.

Kofi Annan, © Ander McIntyre.

FGH: What kind of photographer are you?

AM: I found the fork-lift truck approach to photography a little uncreative. Catherine, my beloved, is French, and we often went to the Institut Français in South Kensington. One distinguished visitor was the great French photographer Willy Ronis, who came in 2002 to introduce his work. I took his photograph à la sauvette, showed it to the Embassy staff, who gave me a job for the next six or seven years, photographing a huge variety of French and British film people. The quantum jump from fork-lifts, and the beginning of what I now do almost exclusively, was the ability to do exactly what I wanted with the beautiful movie stars like Sabine Azéma or Julie Delpy, and great film directors like Nic Roeg or Richard Attenborough. No-one with a diagram of how the shot should be done, what orientation, what lighting, nothing. I took the same approach at the Royal Academy with a series of portraits of architects, which led to a one-man exhibition there. And the same again at the British Library, photographing writers like Chomsky and Steven Pinker. And again, at the Goethe-Institut and the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI, a military/intelligence think-tank).

FGH: What is there in the genre of portrait photography that attracts you?

AM: Scanning electron microscopes just sit there, dead still, unvarying. The beautiful French film-star, with a face that dreams are made on, and the ex-President (ditto, nightmares) - these provide, literally, infinite variety for the photographer. However the subject might think they proffer the same face, the same pose, the PR-sanctioned image, the slightest eye-movement betrays, and allows the photographer to slip inside.

Katrin Jakobsdottir, © Ander McIntyre.

FGH: Does portrait photography inevitably imply glamorisation?

AM: No. It says: ‘look at me, I am worthy of attention’. This renders even the most humdrum subject a little more interesting to look at. Not glamorous.

FGH:The focus is often on the face. The treatment is respectful .. even ethical. Does this make sense?

AM: I recently photographed a President from behind, filling the frame with his clasped hands, and a graphic artist, reflected in a brass doorknob. I even have a self-portrait reflected in a Prime Minister’s eyeball. Institutions like Chatham House do prefer the pictures which hang on their walls to look a bit like the subjects, especially as they tend to make repeat visits, and diplomacy is our watchword.

FGH: I see a variety .. sometimes very close, sometimes full-body portraits..

AM: If I have any kind of aesthetic, it is to do nothing, to get the subject to do nothing. Often at the French Embassy, I would ask for “aucune expression”. I like to be invisible, for the subject not to react as he or she would to a photographer with flash, tripods, lighting, or in a studio. Bailey once said that if he took out a motor-drive, the model would automatically jump around, and if he used a 10 by 8 ( a slow to operate, large-format) camera, they would go into a statuesque Irving Penn pose. I keep my camera behind my back until the last moment and try to get to the subject before they do ‘the pose’ that they have been told to adopt; the one they rehearse in a mirror. If ‘nothing’ is happening, then the subject might start to think about lunch, or their lines, or international geopolitics. So, they forget the rehearsal and drop back to being themselves. Of course, now and again this doesn’t work, and I actually get nothing. It’s a little like being a pickpocket - the success is partly stealing the wallet, and partly the victim not realising until the bill arrives.

Rev. Lucy Winkett, © Ander McIntyre.

FGH: How do you keep your own politics in check? Do you photograph those you like and those you don’t in the same way?

AM: At Chatham House I choose whom I photograph, and we agree that a reasonable approach is to photograph a wide selection of individuals, not just the obvious Presidents and Prime Ministers, but persons from the worlds of business, campaigning charities, NGOs, science, law, etc. This co-incidence of interest extends to the persons themselves. Leaving aside the fact that it is simply not good manners and a breach of trust to make someone look bad because I dislike their stance on fish quotas or renewable energy, the wider imperative is that of diplomacy. Chatham House acts as a diplomatic platform, where speakers, very often representing their countries, put their case, and are questioned by those who might disagree with that case. This is really the only way forward in civil society. So, my very small part is to take ‘my’ portrait, not glamorising or demonising.

FGH: Is photography per se political?

AM: Someone like Godard said ‘everything is a political act’. In line with the above, I would respectfully and diplomatically agree and at the same time disagree with this statement.

FGH: What would you like to share about the creative process? Could you talk about some specific photographs?

AM: When Joe Biden* spoke (before he announced his candidacy for President) I was struck by his straight-backed bearing, and the very sculptural set of his face. The longer I can have to observe how subjects stand, talk, greet people, even drink tea, the better. He seemed to be both rangy and expansive and at the same time, precise and calculated. He has a particularly interesting profile, and it seemed profitable to allow him to look like an inauguration medal. While doing nothing myself, of course, and while he did nothing.

The photograph of Kofi Annan* is an example of one of the great challenges of portrait photography: what do you do when faced with physical beauty? From Jude Law to Katrin Jakobsdóttir, all you have to do is go snap and you have a fine result, but so what? If the point is to get something beyond a pretty surface, then you have to put in a little spadework. While, again, paradoxically doing nothing. Kofi was a hero and will be greatly missed, but I am hoping that the portrait reveals something of his steely grace.

The Reverend Lucy Winkett* is the vicar of St James, Piccadilly, just up the road from Chatham House, where she has spoken at conferences; her approach is remarkably inclusive and diverse, and I photographed her in one of the quiet side aisles of this Wren church, with the amazing Grinling Gibbons reredos and the font where William Blake was christened.

Noam Chomsky, © Ander McIntyre.

FGH: How does this exhibit compare with your exhibitions at the Royal Academy, the British Library, the French Embassy?

AM: Time. My previous exhibitions were just that, installation, vernissage, Roederer, canapés, congratulations, it was nothing, really, and down they came in a month or three. My first batch of portraits had been up at Chatham House for about five or six years; this year being our centenary, we have refurbished the building in interesting ways, and the portraits are planned to be a near-permanent feature. We shall have about 160 pictures up by this August with more planned.

FGH: Is it the same process to photograph a Queen and a commoner? A Prime Minister and a writer?

AM: I might be given less time for one rather than another, but otherwise not really. Photoshop has no favourites.

Tristram Hunt, © Ander McIntyre.

FGH: Your favourite exchanges with subjects? And challenging moments?

AM: I recall discussing The Dick Van Dyke Show with Steven Pinker: I had found the exact episode of this early sixties’ sitcom which was aired at the critical point of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Fascinating conversation with Chomsky about jet lag (he never suffers), and with Sir Richard Attenborough cutting me from the final edit of one of his films (he assured me it was not personal).

Now and again the subject will have an entourage, who may or may not have ideas about where and how the subject should be photographed. My role there is to ease them away from this path, and into the sunlit uplands of my method. Diplomacy again.

FGH: Your website is called Portraits of an Establishment; there are writers, actresses, film-makers, journalists - is there an expansion of the term, beyond those in ‘power'?

AM: The established meaning of the word has fallen away in recent decades. The Establishment was once the Government, the Church, the Army, the Universities, etc. The tipping point was the founding of The Establishment Club, founded by Peter Cook in Soho in 1961. Persons of an interesting background mingled with persons of an interesting foreground. It was connected with Private Eye magazine, and, at the beginning of the 1960s, helped transform the sense of the word. People who create, and make, and change society.

FGH: How do you see the art of photography in this digital age? Many photographers are having a hard time making a living.

AM: They are obviously not trying hard enough. Nineteenth-century photographers would climb mountains and lash themselves to the rigging of a ship in an Antarctic storm, with a camera the size of a Sheraton drinks cabinet, wearing a three-piece tweed suit. And a deerstalker. Perhaps more charitably, we could say that the market-place is crowded; everyone has a camera, everyone takes pictures, everyone is a photographer. Fortunately, most of these people have no idea what they are doing. Evidence of this is the poisonous end of photography where a pose in a Vermeer painting, for instance, is crudely copied in a studio, or a Google Earth printout is manipulated in Photoshop and a brave new artworks are created. Called Appropriation Art, it is also known as stealing someone else’s ideas. There is no need to make feeble copies of existing work. There is an infinity out there, of new things: World is crazier and more of it than we think.

Emma Sky, © Ander McIntyre.

Comments